The Eviction Crisis

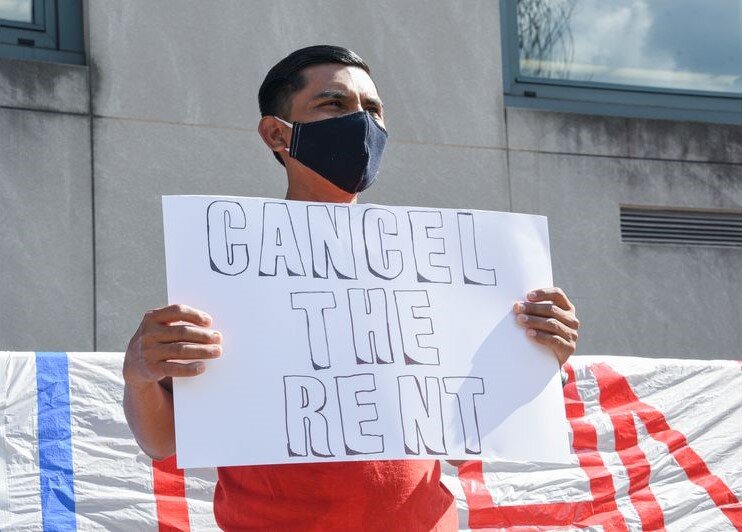

Photo Courtesy of baltimoresun.com

by Natalie C. ‘23

America already had a housing crisis, and COVID only made it worse. The Aspen Institute predicted that about 330,000 Marylanders were at risk of losing their home on July 25, 2020 when the federal moratorium on evictions came to an end. This occured at the same time as the reopening of Maryland courts, which are ready to process pending or already-authorized eviction notices.

On July 24, more than a hundred people marched in Annapolis with tenants, housing advocates, and lawmakers, shouting “CANCEL THE RENT'' and demanding that Governor Hogan take more action to address the eviction crisis. On July 24th, Hogan announced that renters living in state financed properties would be able to receive vouchers which would give them rebates on their rent lasting four months. However, it is undetermined if the crisis will end in four months, and even with the extension it isn’t certain whether most people who are affected will be able to come up with the money on time . Currently, one in five rental units is late on rent due to COVID. Black families, especially those led by black women, are also more likely to face eviction in Baltimore. Not to mention that the financial condition of many Americans was already an issue prior to COVID with about 78% of Americans surviving paycheck to paycheck. In April, about 2.3 million households did not pay any rent, which was about a 135% increase from April 2019.

Evictions can take a heavy toll on tenants for their entire lives. An example would be that being evicted is disastrous for attempts at finding future housing. Landlords in good neighborhoods won’t take a tenant with a flawed record when there is an abundance of tenants with clean ones. The same goes with public housing. Additionally, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia are associated with those facing eviction. Eviction is undoubtedly a stressful situation with very little comparison, that stress can then turn into anxiety and depression. A survey done by the Vancouver Tenants Union further backs up this point. The VTU surveyed 400 tenants about their rental situation and wellbeing; 63% of those surveyed stated that they experienced a range of mental health issues such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression due to their precarious housing situation. Continuing with the topic of housing precarity, where do these people go when they are homeless? To a homeless shelter? Having more people flood in these shelters would overwhelm the means of the shelter and increase the threat of COVID spreading. What about staying in the streets? Sleeping on the streets is incredibly hazardous, 48% of homeless people according to the Guardian have been threatened with violence, 7% have been the victim of sexual assault, and about 80% of homeless people have experienced some sort of crime or antisocial behavior against them. There are 2,500 homeless people in Baltimore and 22.4% of people in Baltimore and because of COVID, these people will be hit the hardest and will be the most vulnerable to the virus. In order to shelter in place to protect oneself and others from COVID, one must first have shelter, a basic necessity that has been forgotten in the nation’s politics and discourse.